11. The Unbearable Lightness of Self-Improvement

Originally published December 2018

We’ve all been willing participants in one of modernity’s largest deceptions — a subversive lie we tell ourselves and each other. (You may not have noticed it, but marketers are absolutely cashing in.) Recently and increasingly, we’ve turned away from material possessions as a marker of a well-lived life, unknowingly having it replaced for us with something just as sinister:

You’ve undoubtedly heard it all before:

Don’t buy a new car, backpack in Thailand for a year. Or,

Leave your high-paying Silicon Valley job and bake cakes. Or,

Stop buying things and buy experiences.

The message here is that earning to spend money on plane tickets to exotic locales is somehow more desirable and impactful for your life than buying a bigger TV. It implies these experiences supposedly lead to increased happiness, because the memories last longer and help you discover parts of yourself that you didn’t know existed.

By extension, it subversively proposes (without outright claiming it) your passion and meaning in life can be found if we look for it hard enough. If you haven’t found it, you just need to look harder, because eventually, you too, can find your life’s purpose. Following this rule, we go to yoga retreats, professional workshops, and read every self-help book you can get our hands on. We go on extended vacations to “find ourselves” or to take pasta-making apprenticeships in Italy. We life-hack, productivity-hack, body-hack, sleep-hack, 6-pack-abs hack our way to perfection.

We falsely believe if we only could just spend money towards the right things and experiences, we’ll be happy.

Then, we’ll find our passion and live a meaningful life.

Then, we won’t have to spend any more money.

We’ll finally be complete.

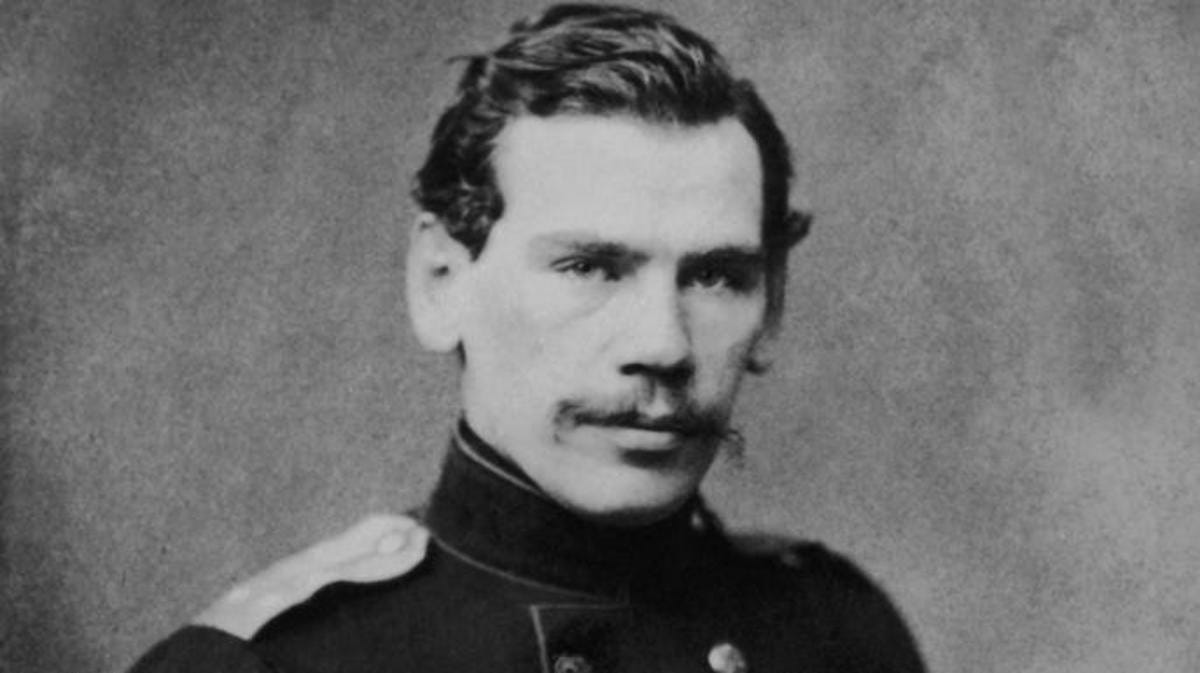

Count Leo Tolstoy was no starving artist. He had everything he could ever want and access to all of life’s pleasures.

In his twenties, he was already well-celebrated and established as a writer and thinker, having enjoyed fame well before War and Peace and Anna Karenina became the talk of the literary world. He was a womanizer, a lush, and a gambler, and despite these vices his wealth continued to grow with little effort on his part. Moreover, he was physically healthy and mentally sharp. He had everything, yet he mired in discontent. For Tolstoy, attainment of every possible measure provided no sufficient meaning. All the land, the wealth, the fame — all the hallmarks of the modern successful life was not enough.

He traveled the world but merely carried his discontent with him.

He received endless praise, to only realize it was mere hollow vice.

Tolstoy had access to endless intellectual companions to share ideas with, but among them, he found a madhouse of self-congratulatory over-confidence, whose inmates were driven by desire for money and praise. Each of them convinced each other that what they were doing was right and for the positive benefit of society. None of them seemed to notice the conditions of their bedlam. And he was deeply troubled by the emptiness and meaninglessness that his peers sought to fill with rationalized hedonism and self-validation.

“Such questions demand an answer and an immediate one; without one it is impossible to live, but answer there was none.”

Halfway into his 30’s, several years past average Russian life expectancy of the time, Tolstoy hoped marriage and a family would cure his ills. “[My life’s pursuit of meaning] was again changed into an effort to secure the particular happiness of my family.” He married a woman 16 years his junior who bore him 13 children (8 survived childhood). She would also be a major player in his later success, helping edit and hand-write Anna Karenina and War and Peace for publication. Even then, into his fifties, Tolstoy kept strands of rope hidden out of fear of being tempted to hang himself and stopped carrying a gun because it would be too easy to end it all.

The wealth, the celebrity, the recognition, a passion for his work, the family — it wasn’t enough.

Take this pill. Lose some weight. Run marathons. Meditate. Keep watching TED Talks and reading self-help books. Lean in. Do power poses in the mirror, take cold showers, eat meat, don’t eat meat, eat kale; no — quinoa; no — açai bowls, no — don’t eat, fasting is better for you. Get a college degree; then a master’s degree; just kidding, college is actually stupid and overrated anyway. Find your passion, because passion is bullshit.

How can anyone keep up?

Discarding the belief in material goods giving our lives meaning, we have traded them in for experiences, under the implicit belief structure that these experiences help us grow. While it may be true, there is no evidence to suggest that sustained growth will ever be enough.

Discarding the belief in material goods giving our lives meaning, we have traded them in for experiences, under the implicit belief structure that these experiences help us grow. While it may be true, there is no evidence to suggest that sustained growth will ever be enough.

With every new fad or experience or lifestyle change comes an immediate rush of excitement from a little bit of self-improvement. When we take communion with these changes, we often believe ourselves to be more virtuous because of our “new” selves and congratulate ourselves for doing the right thing — an alleged net benefit to society. We have come to believe eternal development is progress, the way to achieve completeness. All the while, none of us seem to notice the conditions of our bedlam.

But what we never admit to ourselves is that with every new level of attainment we soon find diminishing returns on its effectiveness, because we’re mere addicts to novelty. We must do more and more esoteric things to stay ahead of the curve. The high never lasts long and gets shorter every time, as the withdrawals get deeper and darker. Things, experiences, partners — none of them are enough. And when the thrill inevitably wears off, we return to the place we were before — or worse.

Take heed: Tolstoy is our canary in the coal-mine. He, who had the means, the intellect, and desire to seek deep purpose and meaning, had come to realize that there could be no such law of never-ending progression. Progress is not an unbound, untenable good. Infinite progress doesn’t signify infinite reward. The continuous seeking of self-development as a means to find purpose and meaning in your life can only result in seeking evermore development to fill the gap of our newfound inadequacies. Moreover, it appears the persistent seeking of meaning through such paths only seems to lead to deeper discontent, which we attempt cure through chasing more novel and grander set of experiences — an unending cycle of a false promise.

The Buddhists have an idea called the Stink of Zen — when we become so enamored with our own enlightenment that we reek of our own enlightenment. It is when one has such an inordinate desire to reach Zen that he becomes addicted to the bliss of repeated meditation or asceticism. By pursuing it with such ardor, one misses the point, like grasping at water to hold it. The idea that we can self-improve ourselves towards perfection is a malady that many mistake for a life purpose. It is unambitious perfectionism masquerading as a cure-all; a fake panacea that is the disease as much as it the temporary fix.

If we are to find meaning in our lives, we must start by accepting and attesting that we cannot find it through the pursuit of things, experiences, or self-improvement. Meaning will not be given to us backpacking in Southeast Asia, reading self-help books, or abstaining from masturbating. We don’t “become better” or find meaning by doing what everyone else is doing. And it will certainly not be given to us by paying someone else to do it for us. When we stop pretending that this is the case, perhaps this is when our true search for meaning can begin.

Referenced in this essay:

A Confession by Leo Tolstoy